What’s it all for? (And wouldn’t it be nice if we knew?)

The case for a national strategy and some nuggets of cheerfulness

‘How to Win an Election’ went on tour this week to Cheltenham for a live recording of the podcast at the literature festival. I learned the town has a motto: salubritas et eruditio, meaning ‘health and education’. Apt for town with a famous school and a historic spa.

By contrast, the closest thing Britain has to a motto is that of our King: Dieu et mon droit, which means ‘God and my right’. The question of what the nation and its government are for is left wide open.

Most people think they know what government is for, which is why the question is never asked. People confidently declare that the ‘first duty of the state’ is (at times)

The protection of its borders

The safety of its citizens

The upholding of the law

The protection of liberty

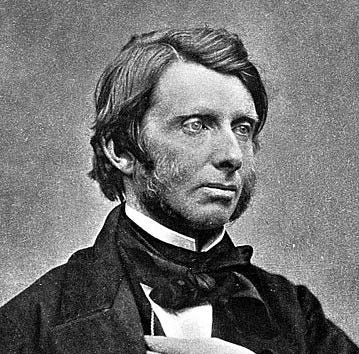

To see that every child born therein shall be well housed, clothed, fed and educated (this one’s the poet and theorist John Ruskin)

The Home Office website says the first duty of government is ‘to keep its citizens safe and the country secure’, without noticing that’s two duties or that they differ from the Ministry of Defence’s definition: ‘to protect its people, territory, economy and interests from internal and external threats.’

In other words, we talk as if the purpose of government is clear and codified, but it is neither. That sounds philosophical, but it’s actually very practical. If you don’t know what you’re trying to do, you can’t tell if what you’re doing works.

Many people argue that the central problem with government is that it is focused on growth only, with casual disregard for health, inequality or the planet. But if this were true, we would not be pouring a quarter of all public spending into healthcare and pensions. There is almost no economic case for funding the healthcare costs of retired people: the case is moral. The truth is worse than the myth that government is a ruthless machine for making money. Government is a muddle.

That’s why I’m inspired by an ambitious piece of work underway at the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford on establishing a long-term national strategy. The idea is simple but radical: make the purpose of government explicit, identify trade-offs, use evidence systematically, and aim for coherence over time.

I like this for two reasons: because it is brave, and it would help shift the relationship between government and citizens in a way that enabled us all to join in.

Be brave

Most people I’ve spoken to about this roll their eyes. They agree it would be wonderful if we could:

break the cycle of political short-termism

create policy stability so businesses and citizens can plan ahead

give confidence to investors to reduce costs

break silos and enable devolved and national government to work together

But then they say it won’t work because:

Politics

Some go further and say it would be anti-democratic to create any kind of strategic plan that could constrain the power of an elected government. It’s certainly true that a National Strategy would have to have deep roots into citizens, Parliament and civil society to have any sense of legitimacy.

But what I love about the team working on this is that they refused to be paralysed by these objections. This is a critical technique for navigating what seem like impossible barriers. If you want to unstick a problem, put the impossible parts to one side and work on the possible. Building up consensus on the easy parts creates relationships that enable you to tackle the difficulties from a new angle. It’s the brave approach to policy making.

Join in

Some readers will have the word ‘Gosplan’ echoing in their head. They will be thinking National Strategy sounds like a ghastly soviet system for micromanaging every widget and workday from an office in Whitehall. If it were: I would be first to the barricades to campaign against it.

But national strategy shouldn’t be about telling people what to do. It should be about telling them what story they’re in - an enabler for a new relationship between citizen and state.

You could see a glimpse of this idea in Labour’s talk of “missions”. It was, in theory, an attempt to move beyond the usual list of short-term pledges and to say: here are the long-term national outcomes we want to deliver together. By mobilising government, business, investors, civil society and citizens themselves behind these common goals, we can make transformative progress as a nation.

But the idea got lost in translation. The missions were boiled down into measurable first steps and familiar, pledge-card-style goals - implementation without inspiration.

A true national strategy would go deeper. It would start with the question: what kind of country are we trying to become? If Britain agreed, for instance, that we wanted to be the world’s clean-energy laboratory, or the healthiest society in Europe, it could influence how everyone, from government departments to councils, investors and citizens, made decisions. Citizens could see their role as participants in a shared project, not just taxpayers and consumers of services.

This kind of strategy doesn’t rely on control; it relies on coherence. It gives government, business and civil society a common frame of reference, so that thousands of small, independent decisions start to reinforce rather than cancel each other out. That’s what makes a national strategy powerful. It’s the foundational infrastructure for a ‘join in’ society.

The purpose I would choose

Sadly, neither God nor my right has granted me authority to choose what the national strategy should be. Nevertheless, if I were to pick a national purpose, I’d be with Cicero: the welfare of the people is the highest law. Government should be optimising for wellbeing.

Frustratingly “wellbeing” has become a suspicious word - seen as woke-coded by the right and dismissed by self-styled pragmatists as fluffy and unserious. The tragedy is that it’s neither. It’s economics at its most grown-up.

Wellbeing, properly understood, is not the opposite of growth. Jobs, income and economic security are among the strongest determinants of life satisfaction. But growth alone is not enough. The wellbeing lens asks whether growth is doing what we want it to do: making people healthier, happier, more secure, more free to live lives they value. It’s a framework that allows us to make better trade-offs: between growth and health, security and liberty, short-term gain and long-term sustainability.

There’s a reason this idea makes some people uneasy. It threatens the comfortable ambiguity in which politics currently operates: the ability to claim success without ever defining what success means. But as a guiding purpose for a national strategy, it has three enormous advantages.

First, it’s coherent. Wellbeing integrates the economic, social and environmental domains rather than setting them against one another.

Second, it’s measurable. We already have decades of robust data and methods to track wellbeing outcomes across the population.

And third, it’s mobilising. People understand it. They can see their own lives and communities reflected in it. It offers a story we can all be part of.

And if we had a national strategy built around wellbeing we’d need a motto. I’ve translated mine into Latin, because it makes it sound more serious that way:

Laetare. Audere. Participare.

Cheer up. Be brave. Join in.

Morsels of Optimism

I have promised good cheer in this newsletter, so each week I want to signpost you to a few people and things that give me hope.

Larger Us is a brilliant organisation that helps build stronger links in and between communities. The founder, Alex Evans, is here on substack where he writes the (surprisingly upbeat) Good Apocalypse Guide. And so is the Chair, Elizabeth Oldfield, who writes about relationships, belonging and human relationships under the banner Fully Alive.

“The most important part of a system is often the person who keeps it from breaking today.” - a beautiful speech by Ron Bronson at a design conference in Oslo.

It’s hard not to be cheerful when you spend time with scientists designing radical solutions to problems. My friends at Zinc, an early-stage venture builder and fund published their impact report this week.

I’d love to know what gave you hope this week.

This has got me really curious. I am intrigued & interested.

Bravo! This really is very good.